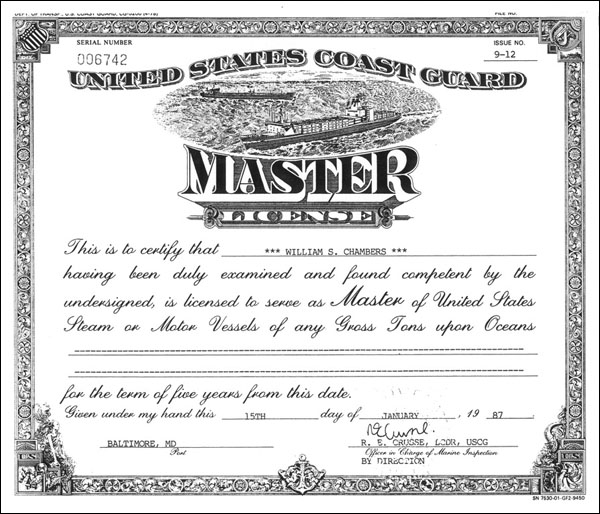

Capt. Chambers was in the steamship business in one capacity or another from 1939 until he

retired in 1992. His last voyage as a merchant marine officer was probably in 1946.

After he graduated from MIT he worked for steamship companies in Havana Cuba and NYC.

Later he went to work for the United States Maritime Administration where he retired

as Director of the Southeast Region of the Maritime Administration.

[Note... The following information and more can be found at the

Veterans History Project

of The Library of Congress.]

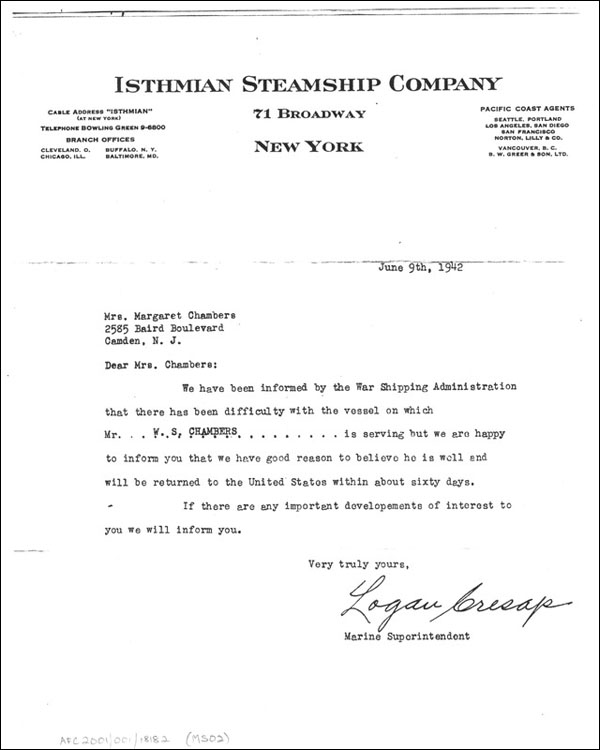

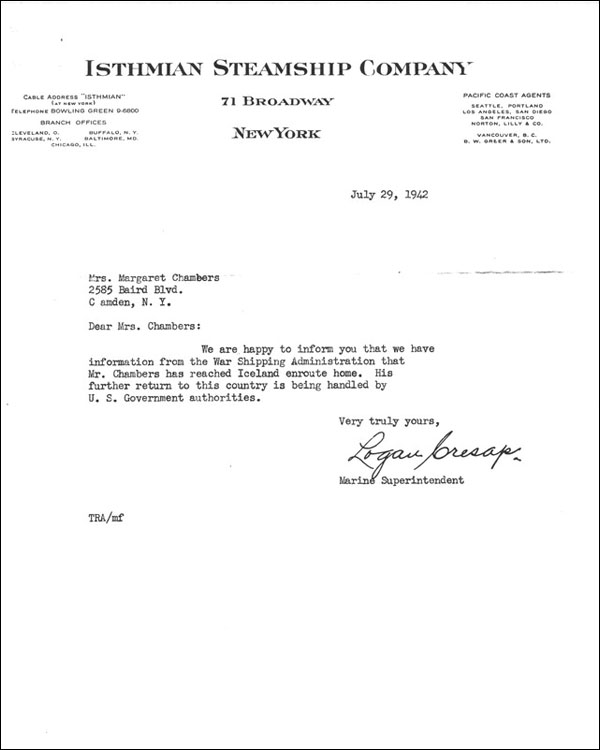

"William Chambers was en route to Hawaii on a cargo ship on December 7, 1941, when his captain

announced news of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Chambers had been in effect training for war

for two years. At 18, he entered the Pennsylvania State Nautical School in October 1939,

shortly after WWII broke out in Europe, and the school had its students learn the ropes on

different vessels of the U.S. Navy. During the war, Chambers made many dangerous voyages,

none worse than a 1942 trip to the Soviet Union on which he lost three ships to torpedoes

or mines. At war’s end, he was still at sea, carrying supplies for the invasion of Japan

which were never needed."

[Note... The following is an excerpt from a 2004 interview of Capt. Chambers for the Veterans History Project.]

"...

Kathryn Chambers Torpey:

Your first voyage as Junior Third Mate was on the SS Steelmaker. You were on board that vessel

when the war started. Please tell me about that voyage.

William S. Chambers:

Well, the SS Steelmaker was a cargo ship owned by the Isthmian Steamship Company. We were on a

commercial voyage en route from New York via the Panama Canal to Honolulu. While eating

breakfast before going on the eight to twelve morning watch, the Captain came into the officers

saloon and announced the receipt of a radio message from the U.S. Navy San Francisco to the

effect that Japan attacked Pearl Harbor a few hours earlier and we were to follow sealed orders

the Captain had received in Panama. Upon arrival in Honolulu Harbor on December 15th, we only

heard rumors about what had happened. We were not allowed to see the damage in Pearl Harbor

nor around any other parts of the waterfront. The longshoremen where Japanese. They were

under guard of the military at the time. We were allowed off the ship, but only on the pier

and in the very near vicinity. We were not allowed to go into Honolulu. We returned to San

Francisco in a convoy, which was the first convoy I had experienced. We had a U.S. Navy

signalman on board for communication with other ships. We were shelled by a Japanese

submarine in Kahului Harbor on December 30th, 1941, shortly before we left for San Francisco.

Kathryn Chambers Torpey:

During the rest of the war you sailed in various convoys. Please describe the nature of a convoy.

William S. Chambers:

In a convoy each ship flies a number and the number is visible to all the other ships in the

convoy. For example, if the ship was number fifteen that means the ship was in column one and

row five of the convoy. The convoy commander was a high ranking Naval officer on the lead

merchant ship. The convoy commander would send signals or messages to the other ships and

the other ships were to keep in position on station and be ready to receive orders from the

convoy commander at any time. As to the course and distance and speed and maneuvering,

instructions in the event of an attack, were constantly going back and forth.

Kathryn Chambers Torpey:

Your first voyage in a convoy across the North Atlantic was on the SS Steel Worker

which was also owned by the Isthmian Steamship Company. You were a Third Mate. The ship

departed from Philadelphia on March 26, 1942, en route to Murmansk, Russia. Please tell

me about that voyage.

William S. Chambers:

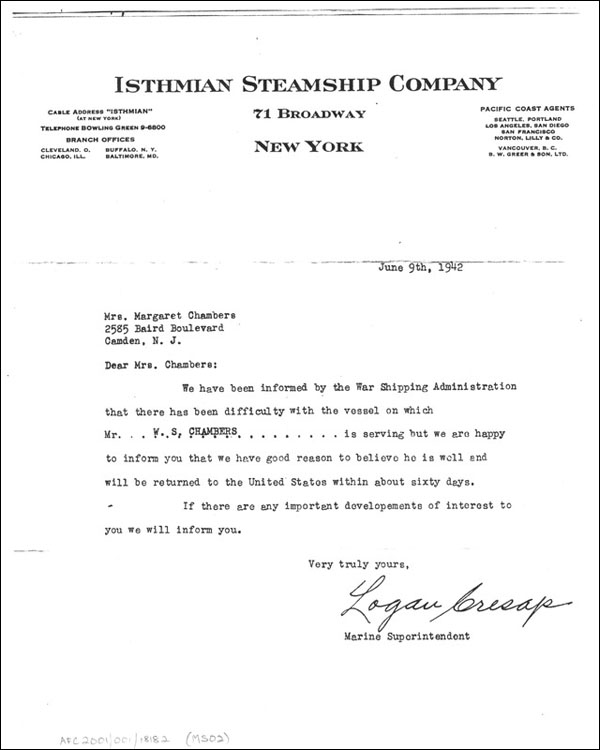

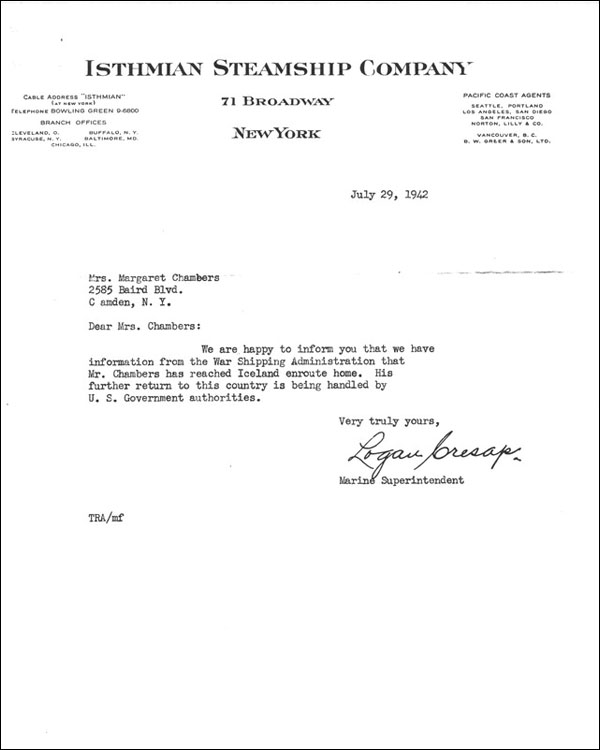

Our ship was loaded with cargo for Russia including 250 tons of explosives. The explosives

were in number five hatch which is at the stern of the ship. The ship was armed with machine

guns to be used by the merchant seaman. There was no U.S. Navy armed guard on board only two

U.S. [Navy] signalmen for communications purposes with the other ships and the convoy

commodore. According to my notes, from May 25th to May 31st we were under continuous air

attack. My notes say that 8 ships were sunk, 3 were hit and made port, many damaged from near

hits, 4 enemy planes were destroyed, and many were damaged. When we finally arrived at our

destination in Murmansk, we unloaded the 250 tons of explosives straight away. On our way to

discharge the remaining cargo for Russia at another berth in this great Kola Inlet a heavy

explosion hit number fivehatch which had been loaded with explosives. The ship sank on

June 3, 1942, while navigating through the Kola Inlet. It may have struck a mine, we don't

know. It struck (sic) [sank] in the half an hour. We abandoned ship by the ship's lifeboats

and a British escort vessel picked us up and took the transferred crew members to the

SS Alcoa Cadet. Russian divers subsequently reviewed the cargo plans for the SS Steel Worker

and were able to salvage much of the cargo that could be of military use because the ship

had sunk in water that was less than 100 feet deep. The SS Alcoa Cadet had completely

discharged its cargo and was waiting for orders to proceed to another port or perhaps

back to the United States. As far as the sinking of the ship is concerned [i.e., the

SS Alcoa Cadet which sank on June 21, 1942], the British said it was a mine and the

Russians said it was a torpedo. We could have been... It could have been a mine dropped

from a German plane. I was standing beside my desk in my office (sic) [cabin] when the

ship blew up. I was rescued from a life raft along with the Captain of the ship by a

Russian patrol craft and transferred to a Russian military barracks across the river

from Murmansk. I remember that I had gotten my first wristwatch when I graduated from high school.

Both my wristwatch and my original seaman's certificate and other papers went down with

the SS Steel Worker on June the 3rd, 1942.

..."

|