(Dictated to his grandson, Ross Dinsmore, May 28, 2005, and edited by his son,

Douglas, June-August, 2005.)

In 1937, I hitchhiked from my home on a farm in southwestern Pennsylvania to Baltimore, with the intention of going to sea to see the world. I was inspired in part by the writings of Richard Halliburton. In Baltimore, until I could get my papers to apply for a sea job, I drove a truck for a fish huckster to deliver fish to neighborhoods in Baltimore. Eventually, I received my papers, and signed on as an Ordinary Seaman (OS) with the Bull Line, on the SS Barbara. The ship went to the Gulf of Mexico, the West Indies, and the East Coast. Then I moved to the SS Clara, also with the Bull Line. We went to the same area that the SS Barbara covered.

After two years with the Bull Line, I took an examination to become an Able Seaman (AB). The exam consisted of knowledge about a ship. I then went to Isthmian Steamship Company to apply for a job. I had heard, in my two years with Bull Line, that Isthmian was the best line for which to sail, and they went all over the world.

The only Isthmian ship in Baltimore at that time (1939) was the SS Steel Age, which was docked a couple miles from the inner harbor, near Fort McHenry. I walked there, and asked the chief mate for a job. He said that he had an OS that probably wouldn’t show up, and if I would come at midnight, and the sailor hadn’t shown up, I could have his job. I returned to my room and packed my duffel and walked back to the ship, arriving at midnight. The other sailor didn’t come, so I had a job with Isthmian. We were five months on the first trip, which went to India. Even though I was an AB, I had to sail as an OS to get a job with Isthmian. Captain of the SS Steel Age was Ralph Jones. Second trip to India, I was an AB.

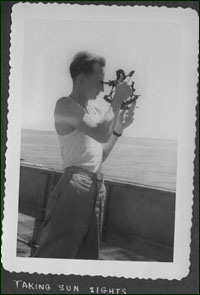

In 1940, I went to the SS Fairfield City, as an AB. I had checked the schedules of Isthmian ships, to see the one that went to the most interesting (from my point of view) places. The SS Fairfield City, with Captain Cecil Fitzsimons, was the best choice. We went around the world in six months. It was on the SS Fairfield City that I met Allen McAmis (Mac), who would become a good friend. He and I aspired to be officers, and in our down time, grilled each other on the knowledge that it would take to pass the officer’s exam. Another sailor, Reams, also became a good friend. The three of us had many adventures in the many ports where we stopped. We were on the SS Fairfield City for two round-the-world trips in a year. We sailed out of New York.

Returning to New York, Mac and I sat for the third mate’s license exam. We both passed it. I was assigned to the SS Birmingham City as 4th mate in 1941. Captain was Michael Francis Barry (Iron Mike). We went along the East Coast through the Panama Canal to the West Coast back through the Panama Canal to Great Britain then back to New York. On the second trip, we went to Rio De Janeiro, considered to be the most beautiful harbor in the world at that time. On the SS Birmingham City, I met George Keenley (Sparks), who would become a good friend.

In the late fall of 1941, I was assigned as third mate on the SS Tuscaloosa City, with Captain Harold Hendrickson. While I was waiting for orders, Ralph Jones visited me, and asked me to sail with him on the SS Steel Age again, this time as third mate. I declined, largely because I did not particularly care for Captain Jones. I didn’t dislike him personally; I just would rather not sail for him. We finally sailed for Calcutta from the SS Tuscaloosa City’s homeport of New Orleans on December 1st, 1941.

Six days after we set sail, World War II started for the United States. On the return trip, May 4th 1942, our ship was sunk by a German sub in the Caribbean. I was not on watch, but relaxing on the aft deck, when we could hear a diesel engine. We thought it had to be a submarine, as we couldn’t see it, but could hear it getting closer. The Captain ordered a zigzag course, but still the diesel engine was getting louder. I went to the Captain and asked why we weren’t trying to steer dead away from the sound, or why we weren’t radioing for help. Captain Hendrickson replied that he had his orders, and they were to stay on course and observe radio silence. I went below to rest, because I would be on watch later.

I had fallen asleep in my bunk when the first torpedo hit. The explosion was deafening, and the ship listed sharply. The bulkhead door slammed shut, and with great difficulty, I pried it open. A second torpedo had landed on deck. We all headed for my lifeboat. I was in charge of the No. 4 boat. But as it was lowered, the ship was still moving forward, and the lifeboat capsized and broke into two, putting five of us in the water. The ship was able to pick up the other four, but I was left, sitting on a piece of capsized lifeboat as the ship continued to steam away, down by the bow.

I watched as the ship was hit again by another torpedo, then slowed, and went down by the bow. By this time, the ship was a ways away from me. I did not see that the crew had successfully launched another lifeboat, and could not see it after the ship went down. For about twenty minutes, I believed that I was the sole survivor, sitting on a piece of broken lifeboat. I knew that, without the ability to set a sail and steer, I would be unlikely to be found. My despair was suddenly broken by the surprise of the conning tower of the German submarine (U-125) breaking the surface a few yards from me.

The submarine surfaced, and the captain came out with a seaman. The captain spoke perfect English. He asked if I were all right, and I said, yes, I was. Then he asked if I wanted to come on board. Preferring death to becoming a POW, I replied, “No, sir!” He then said that the rest of the crew was in another lifeboat, and that he would tell them where I was located. The submarine then motored away. The other lifeboat came and picked me up.

Although all the crew survived, the Captain related that the Chief Engineer had not shut down the engines, leading to the destruction of my lifeboat. The Captain had to order the Chief Engineer below to shut off the engines, so they could try to launch another lifeboat. The Chief Engineer had been reluctant to go below in a sinking ship, but eventually did so.

Several hours later, we were picked up by a ship, which took us to Cartegena, Columbia. Later, we flew on a Pan American Clipper to Miami, Florida. Then we took a train to New York. We were given several days off, while a new assignment was sorted out. In New York, I learned that the SS Steel Age had been sunk with all hands lost. I thought of Captain Jones and his offer.

My mother was going to meet my ship in New Orleans, but we never made it there. She went each day and sat in the Isthmian offices, day after day until they told her the ship was sunk and I was in New York. Then she took a bus to meet me in New York.

Some time in June of 1942 I was assigned to the SS William Whipple, a Liberty ship operated by Isthmian, as a 3rd officer; Fitzsimons again was my captain. I went to San Francisco by train, as the ship was being built there. After I got to San Francisco, we waited a week to get the ship from the ship yard and then another week to get supplies for the ship. Then we set out for the South Pacific. As we passed the last buoy heading out to sea, I despaired that I would ever see my country again. We were headed in a contested area with a dangerous cargo, and I thought I would not survive the trip.

We went to New Caledonia. Then we steamed north to Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides. Our cargo was 5,000 tons of 500-pound bombs (20,000 bombs), and 5,000 tons of aviation fuel (in 55 gallon drums), for Army Air Corp bombers on Guadalcanal. From Espiritu Santo, we went to a station off Guadalcanal. We unloaded our bombs and fuel into barges that were taken ashore. It took us nearly three months to unload our cargo, as we could unload to one barge at a time, very slowly. In addition, we were often sent back to Espiritu Santo when enemy action appeared imminent.

Once, in November of 1942 after being sent back to Espiritu Santo, we were again on our way to Guadalcanal, steaming alone, and I was on watch. A battle fleet appeared on the horizon, and I rang for general quarters. Captain Fitzsimons, who didn’t particularly care for me, asked why I had rung general quarters. I pointed to the approaching battle fleet. He said, “Why they’re ours!” I asked him how he could tell. But they were ours, a battered fleet of cruisers and destroyers, and they passed little more than a hundred yards to port. One ship, the cruiser USS San Francisco, had serious damage, with a tilted mast, drooping guns, and nearly the whole bridge a blackened, twisted mess. As we, on our floating bomb, passed the fleet, they flashed in Morse code, “look out for submarines”. We wondered why we couldn’t have one of the undamaged destroyers to guard us, but the battle fleet continued. We also wondered how a (comparatively) lightly armed merchant ship would fare if that’s what happened to a cruiser. But, later we learned that, at great cost, the cruisers had gone up against the battleships of the Japanese battle fleet, and had driven them back, and we were safe to proceed and unload.

After we finished unloading, we sailed to Valparaiso, Chile, where we loaded 10,000 tons of nitrates and took it Baltimore. There I sat for my 2nd mate’s examination and passed it and went to New York. Again, I went to San Francisco, this time to receive the SS James Ives, another Liberty ship. Again, Iron Mike was my captain. We carried general cargo in it to Sidney, Australia, then to Perth, and finally to Calcutta. The voyage began in January or February of 1943. In Calcutta, 10,000 tons of magnesium ore was loaded, necessary for high quality steel. Back to Perth then the Great Circle route around to the Panama Canal, rough trip. We went through the canal to Baltimore, for a total of seven months.

Iron Mike distrusted his Liberty ship, and loaded most of the ore low, putting less on the tween decks. As a result, the ship rolled like a bell in the fierce storms that come off of Antarctica on the Great Circle route. One night, a forward boom came loose, and Iron Mike called me, and asked me to take a volunteer and secure the boom in the midst of a storm, the ship rolling and pitching, waves washing over the deck. We did it, but it was the most frightening thing I did in my career at sea.

Iron Mike liked me, and often confided in me. If he lost his “cheaters” (glasses) or his “grinders” (false teeth), he would ask me to go look for them in his cabin. He often came out to talk to me on the second watch, giving me advice and telling me stories. He once told about the sinking of the SS Birmingham City. He had put on his life jacket, but was determined to go down with his ship, hanging on to railing. But just as he couldn’t hold his breath anymore, a large air bubble caught him and shot him to the surface, and he was rescued, which he took as Divine intervention.

Once, Iron Mike came to me and said that he had $2,000 dollars, and couldn’t find his money. Would I look for his money? I went in his cabin and looked everywhere, but I couldn’t find it. Then I sat down at his desk and looked around. I saw his Bible on the corner of his desk. I picked it up, and flipped through it. There, in the Psalms, one bill was in each page. He had stashed his money in his Bible, and forgot it.

We had just been out of San Francisco for about three weeks, when the radio operator came to me with a telegram for Iron Mike. I said that he should give it to him himself, as he usually did. The radio operator then said, “Read it.” It was a telegram from the government, regretting to inform Iron Mike that his son, a Navy pilot, was missing in action. I took the telegram to Iron Mike, and he took it from me and read it, and put it on his desk. He never mentioned it, and continued about his duties.

Iron Mike encouraged me to continue up the ladder, to sit for my 1st mate’s license. He said that being a successful captain took “lots of guts and a bit of Irish luck.”

Back in Baltimore, I sat for my 1st officer’s examination. Passing it, I was assigned to another Liberty ship, the SS W.W. McCrackin, with Captain George Skelton. We received the ship in Portland, Oregon. From the later part of 1943 to the earlier part of 1945 I was on the ship, over 22 months. Our first trip, from Portland to New Caledonia and then to San Francisco carrying war supplies, was uneventful.

The 1st officer was responsible for keeping the ship in order. When we arrived in San Francisco, the Navy inspection team told Captain Skelton that the SS W.W. McCrackin was the cleanest ship they had ever seen.

On the second trip, which would occupy the rest of the time that I was on the SS W.W. McCrackin, we became a close support ship for MacArthur’s invasion forces. Other than the sinking of the SS Tuscaloosa City, I had not been under fire, even despite the three months off Guadalcanal. The SS W.W. McCrackin came under fire 75 times, and single-handedly shot down one Japanese plane.

All but one of the attacks were air attacks. Some of them were decoy attacks, intending to draw fire away from the main attack. However, as we approached Finschhafen, New Guinea, with general supplies in our holds, three attacks came directly for us. We were steaming alone, as Captain Skelton did not like the constraints of the convoys. He believed that we were safer out where we could maneuver. The SS W.W. McCrackin had two five-inch guns, one fore and one aft, and two sets of 50-calibur machine guns.

The fighters came first, diving straight down at us with their guns firing. Bullets bounced everywhere. I stayed on the flying bridge with my helmsman and the Armed Guard officer; although the bridge was armored, you couldn’t see anything from in there. Then the torpedo planes and dive-bombers would come at us. We could put up quite the fireworks, and continuously maneuvered to present the smallest target to the attackers. The planes never hit us, ether with torpedoes or bombs. There were many near misses though.

At that time, we were transporting a unit of Army stevedores. They would not listen to any officers, either theirs or us. The first few air attacks were decoy attacks, and although ordered below, the stevedores ignored us. However, when approaching Finschhafen, the stevedores again ignored my order to go below. When the Japanese fighters dived on us, and the bullets began bouncing around, they panicked, and nearly killed themselves trying to go below. Several dived headfirst into open hatches, not waiting to go down the ladders. After that, at the call for general quarters, they went below.

A few days later, in the small harbor of Finschhafen, an aircraft carrier had arrived. It was docked, loading fuel, supplies, and ordinance. Then they pulled out, and we pulled in to the same dock (there was only one dock in Finschhafen at that time). Minutes later, a Navy reconnaissance aircraft radioed that a Japanese bomber was on its way. Our Armed Guard were ready, and suddenly the bomber appeared low over a mountain at the edge of the harbor, heading straight for us. We opened fire. The bomber dropped its bombs, but they missed, and it continued on into the middle of the harbor on fire, hitting the water. Gradually, the fire went out, and the airplane sank. We were credited with shooting down the bomber, as the Navy pilot said that the first ship that fired hit it, and we were the first that fired. The Japanese probably had intelligence information, and were likely after the aircraft carrier, rather than us. Still, it was a near miss, as the bombs splashed our aft gun crew.

We then went to Sydney, Australia, and loaded gasoline. In addition to our holds full of 55-gallon drums, we had four loaded gasoline trucks lashed to the deck. As we approached Hollandia, New Guinea, we were attacked. The Japanese fighters hit one of the trucks, setting it ablaze. At the Captain’s order, I took a volunteer and we put out the fire, for if it spread to the gasoline in the holds, we would be one big fireball. I backed myself against the mast with a fire hose in each hand. My volunteer used one hose on the other side. We basically washed the fire over the side of the ship. All this time, we were being attacked, maneuvering and firing antiaircraft ordinance. The Japanese fighters came again, this time singling us out, but the Armed Guard kept them away, and we put out the fire. The truck looked pretty bad, though, but we put it in the barge like the other ones.

When we reached Hollandia, the harbor was under attack. The Japanese had dragged artillery to a ridge overlooking the harbor, and were shelling the harbor. The nearest Navy warship, a destroyer, was four hours away. We had the most firepower of any ship in the harbor, and the harbormaster asked us to try to suppress the Japanese artillery. So, for four hours, we steamed back and forth, firing our five-inch guns into the jungle at the smoke puffs from the Japanese guns. The Japanese artillery began to fire at us, rather than at the barges and other ships. They never hit us, and as far as we knew, we never hit them either. Our Armed Guard had a great time, as they were always ready to fire the five-inch guns.

Sparks was 3rd mate on the SS W.W. McCrackin. He built a boat out of scrap lumber in his spare time, as the Captain would not let him use one of the ship’s boats for recreation. Sparks launched his boat with a couple other crew, and hoisted a sail. However, he got out of the harbor, and then the tide was going out. He and his boat were being swept out to sea, and the sun was going down. I asked the captain for permission to take a boat and rescue him. Permission was granted, and I took some volunteers and we made after him, as our boat had a motor. We finally caught up with him just at nightfall and towed him back. The wind had come up, and the sea was too rough to come along side, so we tied up at the stern. The crew dropped a Jacob’s ladder over the stern so we could climb up. We had missed the evening mess, but the cook made sandwiches for us. Sparks presented me with a bottle of cognac afterward for saving his hide.

We were at sea for 16 months straight on the SS W.W. McCrackin, and we took provisions for just six months. Arno Hill, our steward, was a master at finding provisions. He went ashore every place we stopped and bought food. There were over 60 of us, including the Armed Guard, lots to feed. One time, Arno went with Captain Skelton and I ashore on a tug. Arno liked his booze, and often found a bottle while he was scrounging for food. On the way back, he was finishing his bottle on the stern, while the captain and I were on the bridge of the tug. Captain Skelton happened to look back just as Arno tipped the bottle back too far, and fell over backward off the tug. The Captain cried out, “Man overboard”, the tug reversed, and we fished Arno out of the water. Arno, who couldn’t swim, said that he thought “it was the last for little Arno.” Arno stood six-four and weighed perhaps 250 pounds.

We supported the invasion of the Philippines, and then steamed to Seattle. We endured many more attacks. The near misses had taken a toll, as the pumps ran constantly. The SS W.W. McCrackin went to dry dock for repairs.

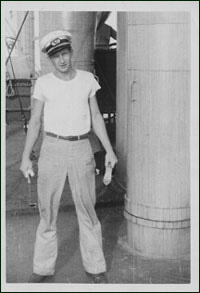

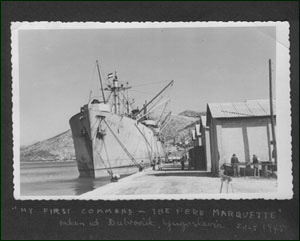

I went to New York, and sat for my master’s examination. After passing it, I was assigned to the main office in New York for a couple of months. Here I met Neysa Elwell (Doug’s mother). We were married after a couple months courtship. Then I was assigned to another Liberty ship, the SS Pere Marquette, out of Galveston, Texas, as master. About half an hour before my train was to leave for Galveston, I was in a bar celebrating my first command, and met Mac. We had not seen each other since we sat for our 3rd mates exam. He, too, had been assigned a ship as master. We had nearly parallel careers. When he saw me, Mac threw his hat in the air, and shouted, “There’ll be some drinking tonight!” However, I had to catch my train. The SS Pere Marquette sailed in March or April of 1945, to the Mediterranean.

Around Gibraltar, shipping lanes had been swept of mines. However, many mines remained in the lanes, presumably duds. During the day, we could steer clear of the mines, but at night, we couldn’t see them, so the mines would bump against the side of the ship. You could hear their triggers going off as they bumped along side. None exploded, but sleep was impossible when we ran into a mine, which we did several times a night.

We put in at several Mediterranean ports. First, we stopped at Naples in Italy. We carried food and other supplies. Then we went to Dubrovnik in Yugoslavia. We stopped at two other ports, then returned to Boston in July 1945.

In Boston, we loaded tanks and crew for the invasion of Japan. However, in August, Japan surrendered. We remained loaded for a couple of months, and then unloaded. On October 12, 1945, I resigned my command. Two weeks later, Neysa gave birth to my daughter Anita. We went to live on the family farm in southwestern Pennsylvania.

|