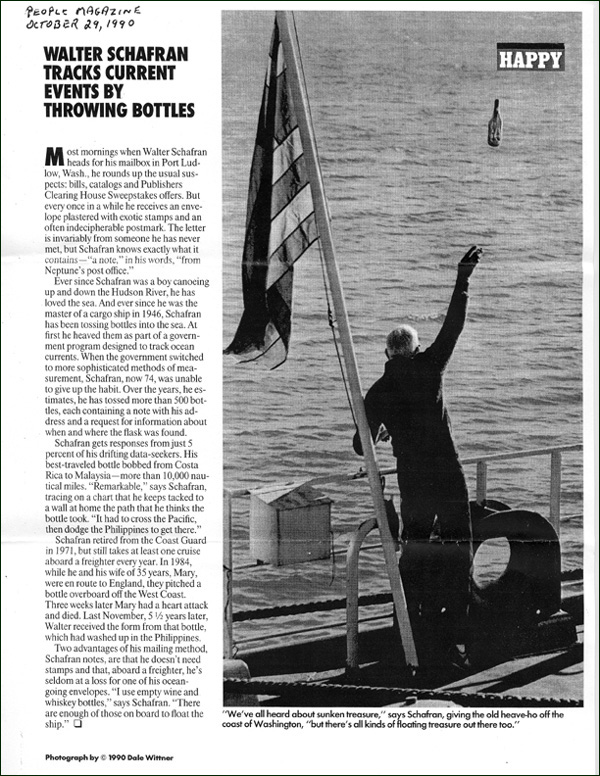

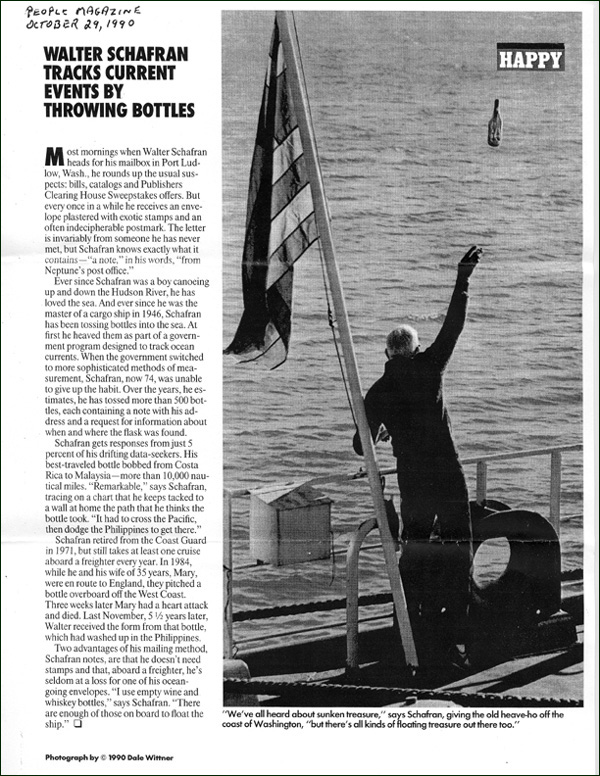

Note..... Capt. Schafran has sent me copies of his A Wartime Voyage

and Notes From Neptune's Post Office. With his permission, I am going to publish some

excerpts from his books in this space.

Note..... Excerpt #1..... I am going to start by publishing

the first three paragraphs of A Wartine Voyage.

A Wartime Voyage

Around The World

36,289 Miles

290 Days

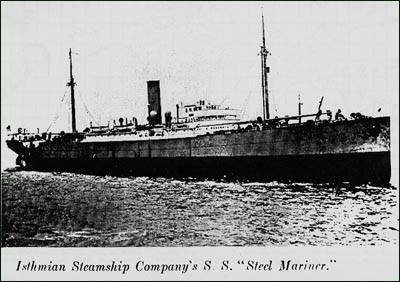

SS Steel Mariner

by W.C. Schafran

DEDICATED IN LOVING MEMORY OF

MY WIFE, MARY,

WHO LOVED THE SEA AND SHIPS

CHAPTER 1 - THE ISTHMIAN SHIPS

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was still searingly fresh in the minds of all Americans,

the pain somewhat eased by the overwhelming victory over the Japanese fleet at the Battle of

Midway in early June 1942, when the Isthmian Steamship Company's SS STEEL MARINER commenced

loading cargo of lend-lease war material in Baltimore, Maryland, for the Soviet Union. She

had just arrived at a loading berth after coming from Bethlehem Steel's Key Highway Shipyard

where a gun had been mounted at the stern, two 20 MM guns on the bridge,

and two 20 MM guns on the boat deck. A U.S. Navy gun crew consisting of one officer and thirteen

enlisted men was to report aboard a few days later. Although traditionally the hulls of Isthmian

Line ships above the waterline were painted gray, the deck houses white, and the funnel, masts

and booms buff, she was now war-time gray all over. This was how I found her when I came aboard

as Second Mate on 7 August 1942.

The SS STEEL MARINER was one of 28 freighters owned and operated by Isthmian Steamship

Company, New York, New York, then a subsidiary of United States Steel Corporation. They were

built in the years 1920 through 1921, 14 by Federal Shipyard at Kearny, New Jersey, and 14 by

Chicksaw Shipbuilding and Car Company at Chicksaw, Alabama.

While not a large ship by today's standards, STEEL MARINER (and her sister ships) was of

average size for her day, being of 5,690 Gross Registered Tons, 3,450 Net Registered Tons,

and 9,400 tons Summer Deadweight. Her other registered dimensions were: Length, 424.2 feet

(about 440 feet overall); Breadth, 56.2 feet; and Depth, 26.5 feet; horsepower was 3,100.

These ships had trim lines and were known throughout the U.S. Merchant Marine as being

“good sea-boats.” And although the company might haggle over a few hours of overtime, it

seldom questioned expenses for the maintenance and upkeep of its ships.

Note..... Capt. Schafran goes on to explain "well deck" and "flush deck" ship

designs.

Note..... Excerpt #2.....

CHAPTER 2 - REPORTING ON BOARD

Normally, when first joining a ship, It is good seaman-like practice to familiarize

oneself with all the parts of the ship and her equipment. I recall that when reporting

aboard a ship for my first assignment as Third Mate, the Chief Officer ordered me to

locate and identify every sounding tube, reach-rod (remote control to an inaccessible valve)

and vent pipe on the weather deck. But this wasn't necessary aboard STEEL MARINER for

I had served aboard sister vessels for several years as able seaman and Third and Second

Mate. I did, however, immediately check the master gyro compass and repeaters and the ship's

chronometers, all of which are traditionally the responsibility of the second mate. The

chronometers, on which celestial navigation depends, must be wound daily at the same time--and

God help the second mate who lets one run down!

Another important responsibility of the second mate is the vessel's charts and nautical

publications which must be adequate for the coming voyage and corrected up-to-date by the

latest Notice to Mariners. Additional in port duties include the supervision of the loading

and stowage of the cargo.

As was noted previously, cargo was being loaded for the Soviet Union. At a time early

in the War, when merchant ships were easy prey to marauding German submarines, I was much

relieved to find that there were no items of an explosive nature in our cargo. It consisted

of disassembled railroad rolling stock--the sides, ends and roofs of box cars were stowed

separately as were the wheels and flatbeds--miscellaneous steel products and some food stuffs.

The cargo was to be discharged at two ports in the Persian Gulf, Bandar Shahpour

(now called Bandar Khomeini) in Iran and Basrah in Iraq, for transshipment to the Soviet Union.

Note..... Excerpt #3.....

One at a time, we stepped up to the table, showed the Shipping Commissioner our license

and/or our seaman's papers and affixed our signatures to both copies of the Shipping Articles

of Agreement. Sitting at the table was the ship's Master, Captain George Georgopoulos, with whom

the agreement was made. And although signing-on signaled the beginning of the voyage for the

crew, for statistical purposes this voyage, Voyage 59, began on 18 July 1942, the day

following the day all inbound cargo from the previous voyage had been discharged.

Captain George Georgopoulos obviously was of Greek descent, and he was no stranger to

me as I had sailed with him as Third Mate on SS STEEL INVENTOR prior to the outbreak of

World War II. Captain Georgopoulos' appearance belied his sharp intelligence, keen

business acumen and capable seamanship. His appearance was far beyond any comparison

with the stereotype Hollywood concept, being less than average in height and somewhat

pudgy, with an olive complexion, black mustache and hair, and a round bald spot appearing

at the top of his head.

Nor did he dress like a captain. His most common attire was a pair of baggy brown trousers,

a shirt with a detachable collar (Do you remember them?) but without the collar and tie,

and an old blue uniform jacket. He smoked cigarettes and had the habit of holding a cigarette

at the very center of his lips. He would speak with the cigarette in that position, the ash

growing longer and eventually dropping on the front of his uniform jacket. But again, his

appearance was deceiving.

Note..... Excerpt #4.....

CHAPTER 3 - PREPARING FOR SEA

19 August 1942 saw the last ton of cargo stowed and secured below decks. We were lucky not

to have had deck cargo. Aside from the normal problems associated with a deck cargo, a

deck cargo during war time created many additional hazards from flying debris should the

ship be struck by torpedo, bomb, or shell. As each hatch was finished, the hatch beams were

lowered into their sockets, the wood hatch covers slid into place, and three tarpaulins

stretched over the wood covers. The overhang of the tarps were neatly folded and tucked

behind cleats welded at an angle to all four sides of the hatch coaming. Then, long,

flat-steel bars, called battens, about 1/2” x 4” x 20', were forced between the cleats

and the tarps. And lastly, several flat-steel cross-battens, each as long as half the

width of the hatch, shaped at one end to catch the flange of the hatch coaming and at the

other end so as to meet at the middle of the hatch and butt against the one from the other

side, were laid across the hatch and bolted together.

This “battening-down” of the hatches is done by the deck department under directions of

the bo's'n. But there is one final job to be done, and traditionally this belongs to the

ship's carpenter. When all battens on a hatch are in place, along comes the carpenter with

a gunny sack of wood wedges and a maul and he will proceed to drive a wedge between each

cleat and side batten, tightly securing the tarps.

With the hatches now secured, the deck department begins to lower and cradle the booms,

stripping and stowing the blocks and runners (the moving wire that raises and lowers the cargo).

When the booms are lashed in their cradles and all cargo handling gear stowed away, the

ship generally is ready to go to sea (Sometimes, if a hatch is not completely filled with

cargo, one or two hatch covers are left open and as a boom is lowered, the running gear

is stripped right into the hatch).

Note..... Excerpt #5.....

So, the night before we were to depart Baltimore I knew that the ship would be anchoring in

New York's Upper Bay. I was born and grew up in New York City, and my parents were still living in

Manhattan, so I telephoned and told my mother that the ship would be anchored in the Upper Bay but

that I would not be permitted to go ashore. I suggested that if she would ride the Staten Island

ferry, which crosses the Upper Bay, she might catch a glimpse of the ship. She told me later

what happened.

Borrowing a pair of binoculars, she boarded a ferry and made a trip to Staten Island, searching

among the many ships at anchor for STEEL MARINER, but with no success. She remained on the ferry

for the return trip and three more round trips, all the time peering through the binoculars at

the ships at anchor, until her actions aroused the suspicions of two naval intelligence officers

who had been observing her. As my mother told it, she was quite startled to be questioned by the

two officers and to be suspected of intelligence gathering for the enemy. The naval officers

weren't quite sure of her explanation that she was only trying to see her son's ship, but they

accepted it, and when the ferry again docked at the Battery, she hurried home.

Note..... Excerpt #6.....(From CHAPTER 4 - UNDERWAY, CHESAPEAKE BAY TO NEW YORK)

Arriving off Sandy Hook the same day, each ship of the convoy took on a pilot and in

single file proceeded to a designated anchorage in Upper New York Bay. If Lynnhaven Roads

was thought to be crowded, Upper New York Bay was unbelievably “chockablock” with anchored

vessels, many flying the flags of allied countries. How in the world would my mother ever

find my ship amongst this multitude?

But as it turned out, it wasn't even necessary. Amazingly, the purser and I, because we both

had family in New York City, were given permission to go ashore. Because of the rapid build

up of the Merchant Marine, many of the men manning the ships had never been to sea before,

and the purser was one of them. He had been to one of several schools run by the federal

government and had been issued a uniform. He was eager to impress his family and neighbors,

so when the water taxi pulled alongside the gangway, he emerged in full uniform.

The water taxi called at several anchored ships before heading for its dock on the East River

side of the southern tip of Manhattan Island. It was now growing dark. Mooring outboard of

several water taxis already at the dock, we had to cross all of them to reach the dock, an

old wooded structure which looked like it had been there from when the Dutch governed New

York. I was ahead of the purser and jumping the short distance from the last boat rail to the

dock, started walking up the dock. After taking a few steps (it was now dark), I saw his uniform

cap on the dock alongside an opening in the dock surface made by two broken planks. A few seconds

later the purser came clawing his way up through the opening, having jumped from the boat rail

right through the opening and into the dirty East River. Needless to say his uniform was ruined,

but miraculously he had missed all the structural members beneath the dock and was unhurt.

|